Virginia Opossum

| Virginia Opossum[1] | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Didelphimorphia |

| Family: | Didelphidae |

| Subfamily: | Didelphinae |

| Genus: | Didelphis |

| Species: | D. virginiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Didelphis virginiana (Kerr, 1792) |

|

The Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana), commonly known as the North American Opossum, is the only marsupial found in North America north of the Rio Grande. A solitary and nocturnal animal about the size of a domestic cat, it is a successful opportunist and is found throughout Central America and North America east of the Rockies from Costa Rica to southern Ontario (it was also introduced to California in 1910, and now occupies much of the Pacific coast); it seems to be still expanding its range northward. Its ancestors evolved in South America, but were enabled to invade North America in the Great American Interchange by the formation of the Isthmus of Panama about 3 million years ago. It is often seen near towns, rummaging through garbage cans, or lying by the side of the road, a victim of traffic.

Contents |

Name

The Virginia Opossum is the original animal named "opossum". The word comes from Algonquian 'wapathemwa' meaning "white animal", not from Greek or Latin, so the plural is opossums. Colloquially, the Virginia Opossum is frequently called simply possum. The name is applied more generally to any of the other marsupials of the Didelphimorphia and Paucituberculata orders, which includes a number of opossum species in South America.

The possums of Australia, whose name is derived from a similarity to the Virginia Opossum, are also marsupials, but of the order Diprotodontia.

Description

It is the largest member of its genus, family and order and is the largest of the opossums. They are typically 15–20 inches (38–51 cm) long and weigh between 9 and 13 pounds (4–6 kg). Their coats are a dull grayish brown, other than on their faces, which are white. Opossums have long, hairless, prehensile tails, which can be used to grab branches and carry small objects. They also have hairless ears and a long, flat nose. Opossums have 50 teeth and opposable, clawless thumbs on their rear limbs.

Opossums have thirteen nipples, arranged in a circle of twelve with one in the middle.[3][4]

Tracks

Virginia Opossum tracks generally show five finger-like toes in both the fore and hind prints. The hind tracks are unusual and distinctive due to the opossum's opposable thumb, which generally prints at an angle of 90 degrees or greater to the other fingers (sometimes near 180 degrees). Individual adult tracks generally measure 1⅞ inches long by 2 inches wide (4.8 × 5.1 cm) for the fore prints and 2½ inches long by 2¼ inches wide (6.4 × 5.7 cm) for the hind prints. Opossums have claws on all fingers fore and hind except on the two thumbs (in the photograph, claw marks show as small holes just beyond the tip of each finger); these generally show in the tracks but may not. In a soft medium, such as the mud in this photograph, the foot pads will clearly show (these are the deep, darker areas where the fingers and toes meet the rest of the hand or foot, which have been filled with plant debris by wind due to the advanced age of the tracks).

The tracks in the photograph were made while the opossum was walking with its typical pacing gait. The four aligned toes on the hind print show the approximate direction of travel.

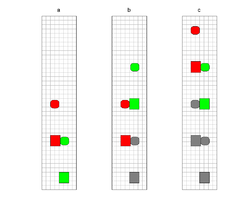

In a pacing gait, the limbs on one side of the body are moved simultaneously, just prior to moving both limbs on the other side of the body. This is illustrated in the pacing diagram, which explains why the left-fore and right-hind tracks are generally found together (and vice versa). However if the opossum were not walking (but running, for example), the prints would fall in a different pattern. Other animals who generally employ a pacing gait are raccoons, bears, skunks, badgers, woodchucks, porcupines and beavers.

When pacing, the opossum's stride generally measures from 7 to 10 inches, or approximately 18 to 25 cm (in the pacing diagram the stride is 8.5 inches, where one grid square is equal to one square inch). To determine the stride of a pacing gait, measure from the tip (just beyond the fingers or toes in the direction of travel, disregarding claw marks) of one set of fore/hind tracks to the tip of the next set. By taking careful stride and track-size measurements, one can usually determine what species of animal created a set of tracks, even when individual track details are vague or obscured.

Behavior

The Virginia Opossum is noted for its reaction to threats, which is to feign death. This is the genesis of the term "playing possum", which is used to describe an attempt to pretend to be dead or injured with intent to deceive. In the case of the opossum, the reaction seems to be quite involuntary, and to be triggered by extreme fear. It should not be taken as an indication of docility, for under serious threat, an opossum will respond ferociously, hissing, screeching, and showing its teeth. But with enough stimulation, the opossum will enter a near coma, which can last up to four hours. It lies on its side, mouth and eyes open, tongue hanging out, emitting both a green fluid from its anus and an odor putrid to most predators. Besides discouraging animals who eat live prey, playing possum also convinces some large animals that the opossum is no threat to their young.

Opossums are omnivorous and eat a wide range of plants and animals such as fruits, insects, and other small animals. Fruit of the persimmon tree is one of the opossum's favorite foods during the autumn.[5] Opossums in captivity are known to engage in cannibalism, though this is probably uncommon in the wild.[6] Placing an injured opossum in a confined space with its healthy counterparts is unadvisable.

The Virginia Opossum does not hibernate, although it may remain sheltered during cold spells.[7]

Perhaps surprisingly for such a widespread and successful species, the Virginia Opossum has one of the lowest encephalization quotients of any marsupial.[8]

Life span

Opossums, like most marsupials, have unusually short life spans for their size and metabolic rate. The Virginia Opossum has a maximal life span in the wild of only about two years.[9] Even in captivity, opossums live only about four years.[10] One island population that had presumably been isolated for thousands of years without natural predators was found to have evolved up to 50% longer life spans than what is usual in mainland populations.[11]

Relations

Like raccoons, opossums can be found in urban environments, where they eat pet food, rotten fruit, and various human garbage. Though many humans mistakenly consider opossums to be rats, opossums in fact are not closely related to rodents at all, rarely transmit diseases to humans, and are surprisingly resistant to rabies, due mainly to their lower body temperatures when compared to most placental mammals.

Although it is found throughout the country, the Virginia Opossum's appearance in folklore and popularity as a food item has tied it closely to the American Southeast. In animation, it is often used to depict uncivilized characters or "hillbillies". The main character in Walt Kelly's long running comic strip Pogo was an opossum. In an attempt to create another icon like the teddy bear, U.S. President William Howard Taft was tied to the character Billy Possum.[12][13] The character did not do well, as public perception of the opossum led to its downfall.

References

- ↑ Gardner, Alfred L. (16 November 2005). "Order Didelphimorphia (pp. 3-18)". In Wilson, Don E., and Reeder, DeeAnn M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols. (2142 pp.). p. 6. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=10400045.

- ↑ Cuarón, A. D., Emmons, L., Helgen, K., Reid, F., Lew, D., Patterson, B., Delgado, C. & Solari, S. (2008). Didelphis virginiana. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 28 December 2008. Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- ↑ With the Wild Things - Transcripts

- ↑ Raising Orphaned Baby Opossums

- ↑ Sparano, Vin T. 1998. Complete outdoors encyclopedia: revised and expanded. (Preview online version available at Google Books.) [1]

- ↑ Cannibalism in the Opossum. Opossum Society. Last accessed May 07, 2007.

- ↑ "Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana". eNature.com. Shearwater Marketing Group. http://enature.com/fieldguides/detail.asp?allSpecies=y&searchText=opossum&curGroupID=5&lgfromWhere=&curPageNum=1. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ↑ Ashwell, K.W.S. (April 2008). "Encephalization of Australian and New Guinean Marsupials". Brain, Behavior and Evolution (S. Karger AG) 71 (3): 181–199. doi:10.1159/000114406. ISSN 0006-8977. PMID 18230970.

- ↑ [2] accessed Oct. 15, 2007

- ↑ [3] Accessed Oct. 15, 2007

- ↑ Accessed Oct 15, 2007.

- ↑ Possum Politics. 'Possum Network. Last accessed November 19, 2006.

- ↑ Political Postcards. Cyberbee learning. Last accessed November 19, 2006.

- Brown, Tom, Jr. Tom Brown's Field Guide to Nature Observation and Tracking.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||